#!@*-knows-how-long voice, please.”

From The New Yorker, July 2020

By: Abigail Murray, PsyD

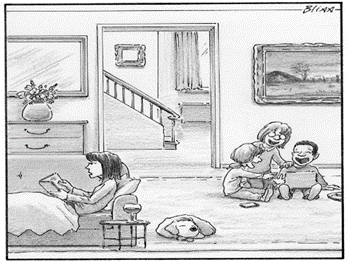

It’s a well-documented and widely recognized phenomenon that when humans undergo tremendous stress, they may revert to early life defenses. This is believed to be a largely unconscious process, one which can be intuited through the behavior rather than indicated by communication. In children, regression takes form in increased clinginess, difficulty separating, tantrums, bedwetting, changes in eating/sleeping, lowered distress tolerance, withdrawing from generally liked activities, or atypical aggression. Numerous psychologists have written on the topic since mid-March, positing suggestions for how to manage when your kids regress.

But why would much be different for parents? In reality, it’s not different but is laced with a different kind of shame. Parents have had numerous roles foisted upon them (teacher, camp “counselor” nonstop playmate); not only that, they have had to somehow stretch themselves to meet these dizzying demands with little objection. This leads to feeling resentful, even rageful. While we love to be needed by our little ones, you may notice your tolerance for being needed is threadbare, your patience is quite a bit lower, and well….you’re acting like a child! Reacting in ways which are out of proportion to any specific trigger or event!

By taking the time to quickly review some basics, we can refresh our empathy for ourselves and our children.

1. Identify what is going on

Being able to notice your signs of emotional regression is the first step. Cultivate self-examination and self-talk in which you draw a nonjudgmental connection between your yelling and the underlying feelings. Are you scared? Anxious? Overwhelmed? Hungry? Dehydrated? What happens when you feel each of these? Does this situation remind you of a situation from the past, and if so what was going on then? The sooner these connections are made conscious, the more quickly you can disengage or opt for a different way of expressing your frustration.

2. Validate being imperfect and human

While it is important your children experience the world (and you) as meeting their needs consistently, this does not mean every single time. Their attachment to you can weather moments where you aren’t as attuned, can’t fulfill a need perfectly, or even miss a sign of a need completely. Recognize that this validation is not to make it “okay” if you feel you failed but rather to encourage necessary flexibility and acceptance in yourself (and therefore your kids). Removing the shame around it enables shifting the dynamic.

3. Develop a way of repairing any ruptures with your kids

Modeling that mistakes do happen and that they can be acknowledged and worked through is powerful. Be explicit with them – “Mommy sometimes gets stressed and loses her temper. It’s okay for her to feel scared/sad/frustrated but it’s not okay for her to take it out on you.” This opens new ways of relating to your kids by normalizing these underlying feelings and putting them to words, ultimately lowering their anxiety. Consider making “do-overs” a fun way you and your kids can reset – pick a song that signals it’s time to restart and give them positive reinforcement when they engage in this practice.

Ultimately, both you and your kids are doing the best you can. Remember to also leave space for regressive moments, to even expect them – we are living through a pandemic, after all.

Leave a comment